Leila Cohn

Center of Formative Psychology of Brazil (CPFB)

Izilda Cristina Martins Cordeiro

Center of Formative Psychology of Brazil (CPFB)

Karina Tiemi Kikuti

Center of Formative Psychology of Brazil (CPFB)

Ronaldo Destri De Moura

Center of Formative Psychology of Brazil (CPFB)

Julia Landgraf Pupo

Center of Formative Psychology of Brazil (CPFB)

ABSTRACT

This article is about the Crisis Assistance Project implemented by a team from the professional groups of the Center of Formative Psychology® of Brazil during the COVID-19 pandemic in the year 2020. The services were done in the online mode, in the Formative Psychology® approach, founded by Stanley Keleman. The project aimed to offer people the means to regulate their emotional responses to the abrupt changes imposed by the pandemic, while learningto form adaptive solutions to the crisis.

Keywords: Formative Psychology, COVID-19 Pandemic, Crisis, Emotional Regulation, Stanley Keleman, Emotional Anatomy, Voluntary Self Influence

1 INTRODUCTION

In contexts of severe social crises, the concern for the mental health of the population becomes more evident. The COVID-19 pandemic was one such crisis, which reached global proportions and was characterized as the greatest public health emergency faced by the international community in recent decades. (World Health Organization [WHO], 2020)

A crisis of this magnitude generates significant changes in different spheres of living for the population as a whole. These changes challenge the emotional stability of the population and the ability to cope with new situations. In this context, emergency efforts are required from professionals in various areas of knowledge to deal with the crisis. (BRASIL, 2020)

In April 2020, members of the professional groups of theCenter for Formative Psychology® in Brazil met to discuss adaptation to remote work: challenges, tools and possibilities. In these meetings arose the desire to make a contribution to society through a free crisis care service.

The online Crisis Care project was organized, which aimed to provide support in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and its unfolding events. The project aimed to help people develop adaptive strategies and ways to influence their emotional responses to the abrupt changes imposed bythe pandemic. All the work was carried out within the theoretical-methodological framework of Stanley Keleman’s Formative Psychology®, which will be briefly presented in this article.

This paper reports on the process of creating and carrying out the Project and contains problems presented, service strategies, orientation offered, feedback from the population served, analysis of the results, final considerations, and the unfolding of the Project

2 FORMATIVE PSYCHOLOGY® AND ITS METHODOLOGY

Formative Psychology®, developed by Stanley Keleman in the 1970s is an evolutionary approach that inextricably links anatomical reality and human existential reality. For Keleman, the human being is an embodied subjective process in constant reorganization of self and subjective experience is grounded in anatomical organization (Cohn, 2007). Changes in anatomical posture influence emotional and cognitive reality. Based on the properties of somatic and neural plasticity and the capacity for voluntary muscular-cortical autoregulation, Stanley Keleman developed a methodology (Keleman, 1987, 2007b), consistent with his way of thinking.

Formative Psychology® starts from the premise that a person can always influence in some way his or her way of being in the world. Formative Workis an educational process that aims to increase voluntary participation in the process of self-organization and personal development.

Voluntary self-influence is done through changes in micro and macro behaviors, involving both muscular-emotional posturesand actions in the world. The Formative Methodology includes the Formative Practice protocol, the making of somagrams, and the organization of new narratives. The Formative Practice works at the micro behavioral level using voluntary micro movements. Formative Work at the macro behavioral level occurs with the implementation of actions in the world, either through the organization of new routines or the restructuring of daily habits.

Formative Practice is an experiential educational process whose voluntary muscular action affects personal experience and creates new possibilities for behavior and experience and new brain maps. The Practice protocol uses voluntary muscular-cortical effort (EMCV) to differentiate degrees of intensity and duration in muscular-emotional postures.(Cohn, 2016).

The Practice protocol contains a sequence of steps that begin by organizing a muscle model of the emotional attitude, immediately establishing a relationship between muscular posture and subjective experience. The next steps involve the creation of distinct gradations in the intensity of the muscular posture, in a coming and going in small steps that broaden the person’s perception of how they do something and the effect of their action. The repetition of the Practice enables the learning of voluntary modulation of emotional attitudes and behaviors, and the stabilization of new brain connections.

3 THE CRISIS CARE PROJECT

3.1 THE CRISIS IN THE PANDEMIC AND THE TRANSITION PROCESS

The COVID-19 pandemic configured a moment of instability, generated a series of questions about the present and the future, and demtanded a broad reorganization in living. The need for distance reduced social contact, and living in a domestic environment became intense. Work and studies became remote, and an adaptation to online life became necessary.

The changes configured a process of transition with experiences of vagueness, instability and uncertainty, and sometimes experiences of disorientation and “not knowing what to do”. For some people, situations like this can generate intense emotional responses, which include fright, startle, fear, anxiety, discouragement, and hopelessness, to a greater or lesser extent.

Stanley Keleman (1979) described transition as a process that simultaneously involves the termination of a habitual way of acting, an experience of elusiveness, and a period of formation and consolidation of new behaviors. This process is dynamic and involves a continuous relationship between stability and instability, organization and disorganization of ways of functioning. The formative process is a journey of learning in small steps with increasing personal participation. The experience of voluntary self-influence disorganizes powerlessness and generates self-confidence and empowerment (Keleman, 2007b).

The sessions in this Project were based on this understanding of the transition process and focused on the voluntary reorganization of macro and micro behaviors, including the Formative Practice protocol, in order to establish more adaptive responses to the new situation.

4 HISTORIES

The Crisis Assistance project took place from May to December 2020. The first three months were dedicated to the preparation and structuring of the project, formation of the work team, development of support materials, training in focal assistance and use of the Wix platform. The services were provided from August to December, when the work was finalized.

5 STRUCTURES

TheProject team was composed of a supervisor, a coordination team, a care team, and a partnership with another similar project, totaling seventeen health and education professionals.

To participate in the Project it was necessary to have at least three yearsof clinical experience, and at least two years of experience in crisis care. All the members of the group were part of the Professional Courses of the Center for Formative Psychology® of Brazil.

The organization of the work involved regular coordination meetings, biweekly meetings and supervisions with the whole team, and biweekly support from the coordination team. To facilitate internal communication, a WhatsApp group and a project e-mail were created.

The Project offered two types of online service: individual and group. The dissemination occurred via the collaborators’ social networks, by means of digital folders.

The following materials were produced:

- The project and its rules of operation.

- Crisis Attendance Manual.

- Description of the care groups.

- Term of commitment of the person attended.

- Attendance report.

- Professional’s final report.

- Promotional brochure

Those interested in the Crisis Assistance should access a link on the electronic platform to schedule an interview. The platform contained an explanatory text about the Project, the available times for assistance, a form with general data, and a commitment term.

6 SERVICES PROVIDED

6.1 INDIVIDUAL CRISIS ASSISTANCE

The Individual Attendance followed a protocol created specifically for the time of the pandemic. The work done aimed to help people learn to exercise voluntary self-influence and included pragmatic guidelines to enable daily well-being.

The service lasted from 1 to 3 meetings via video call or telephone, each lasting 30 minutes. The therapist’s listening included observing the tone of voice, the rhythm and degree of excitability of speech, the problem presented, and the person’s emotional state. The orientations aimed at decreasing the intensity of stress, regulating effort, managing the emotional experience, and structuring a functional routine to help the person come out of the peak of the crisis.

The following questions guided the work of the therapists:

- How is the person responding to the pandemic (emotional attitude, behavior, and thought pattern)?

- What does one need to reorganize in one’s way of functioning to deal with the current crisis?

- How can the person form a functional and adaptive routine to the new situation?

In the first meeting, the therapist sought to understand the general state of the person and how the pandemic impacted his life, investigating his emotional state and its relationship with the current crisis. This included a detailed survey of the person’s routine: sleep patterns, appetite, hygiene, leisure, chores, socialization, support structure, and general health. Specific questions were also asked about changes that had occurred in the person’s family, work, food, financial situation, home care, sex life, pets, and relationship with neighbors. The occurrence of domestic violence and the use of drugs and alcohol were verified.

In this meeting the therapist made concrete suggestions to structure the routine, regulate effort, and modulate stress. These orientations included: regulating food, sleep, and work; organizing moments of conviviality in the family; carrying out physical activity; including leisure moments; regulating interpersonal contact in daily household life; establishingbreak times in daily routines; decreasing demands in daily life and implementing support routines; decreasing exposure to news about the pandemic.

At the end of the session, the possibility of applying the offered guidelines was checked: “Do you think it is possible to use these guidelines in your daily life? Based on the person’s answer, the implementation of the changes was guided in small steps, adding one at a time until the new routines were stabilized.

The second meeting followed up on the initial conversation and adjustments were made based on the person’s feedback. The focus remained on what needed to be reorganized to continue to reduce stress, exercise emotional self-regulation, and manage the crisis satisfactorily.

The Formative Practice protocolcould be used in the second or third meeting, with the intention of developing voluntary self-influence to change emotional states and behaviors. The Formative Practice was applied through exercises that enabled stress reduction and modulation of emotional intensity.

The work was done through hand gestures with the following slogan: “Let’s do an exercise using our hands and observe how you can influence your emotional state.” After the practice there was a conversation about the effect obtained and the person’s ability to repeat the exercise in everyday life to stabilize what was learned and form a new memory.

If necessary, a third visit was scheduled to consolidate what was learned in the previous ones and to make a closing.

6.2 GROUP CRISIS SUPPORT

The GroupWorkshops consisted of 1 to 3 meetings lasting 1h30 and offered seven options with the following themes: Coming out of Isolation; Body Balance; Inner Dance; Mature Women in Times of Pandemic; Women’s Support Group; two Groups for Parents.

The working dynamics of each group were planned by the facilitator according to the group’s theme and the general objectives of the Project. Admission to the group was through an interview with the facilitator via video call or telephone.

7 PROFILESOF THE POPULATION SERVED

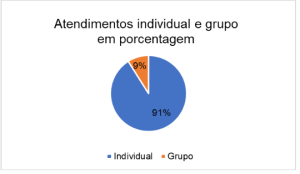

In all, 25 people participated in the Project, making a total of 56 consultations, 51 individual and 5 in groups. The data on the population attended are presented below.

Caption: blue: individual, orange: group

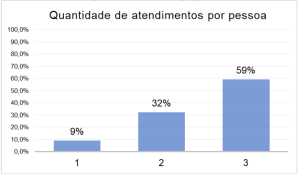

Three consultations were performed for 59% of the people served, two consultations for 32%, and only one consultation for 9%, shown in the graph below:

Caption: number of attendances per person

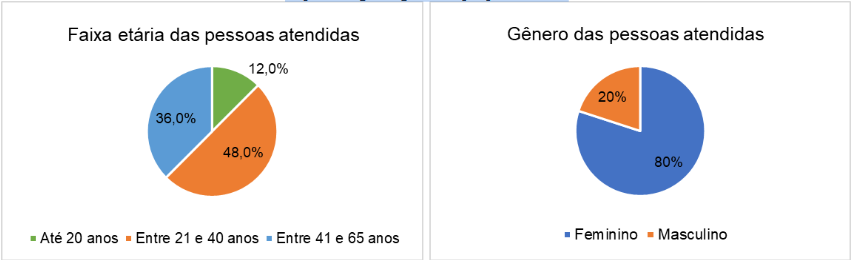

The age range of the people attended was between 13 and 65 years, 12.0% up to 20 years, 48.0% between 21 and 40 years, and 36.0% between 41 and 65 years. 80% were female and 20% male.

Caption: number of attendances per person

Green: up to 20 years, Orange: between 21 and 40 years

Blue: between 41 to 65 y.o.

Gender of the people attended:

Blue: female, orange: male

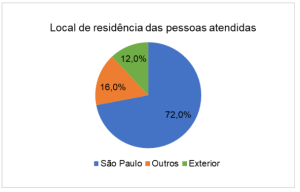

The place of residence of most of the people attended was the state of São Paulo (72%). There was also attendance for individuals in other states (16%) and abroad (12%):

The educational level of the people ranged from Higher Education to Incomplete Primary Education. People had diverse professions and activities: housewife, student, artist, commercial manager, cook, psychologist, teacher, caregiver, seamstress, translator, and anthropologist. Of these people, 65% were working and 35% were not.

None of the people served had COVID-19 in the period that the Project ran, and only one person reported having had contact with someone infected.

8 COMPILATION OF THE DATA OF THE ATTENDANCES

After each service, the therapist would write a report that covered the following topics:

- Problems presented: complaints, disruptive events, emotional difficulties, and symptoms.

- Guidelines offered.

- Effects of the guidance offered.

- The application of Formative Practice and its effects.

- Socialization during quarantine.

- General feedback from the attendings.

The synthesis of the compiled data will be presented below in descending order, starting with the most frequent answers and proceeding to the least frequent ones.

8.1 PROBLEMS PRESENTED

- Conflicts in family relationships.

- Emotional instability mainly increased anxiety. Sadness, body aches, body tension, stress, fear, insecurity, irritability, and discouragement were also mentioned.

- Difficulties in managing routine, sleep disturbances, overload and fatigue accentuated byonline activities, and disinterest in activities done before the pandemic.

- Parents’ difficulties with the constant presence of their children at home and problems with online school life.

- Loneliness, difficulties with social isolation and prolonged confinement.

- Important changes: changes at work, moving house, illness, loss of acquaintances, and marital separations.

- Constant worries about family, future, stability, and financial and professional difficulties

8.2 ORIENTATIONS OFFERED

- Structure the new routine by setting clear limits for activities and include breaks in between, in order to regulate effort and reduce stress.

- Set schedules for work and rest, sleeping and waking up, meal planning and preparation with attention to food quality.

- Create routines considering the needs of each member of the household.

- Improve communication in the household through conversations and exchanges.

- Resuming or starting physical exercise with or without online guidance; moving and walking in open space safely.

- Decrease internet and cell phone usage time; and end online activities at least one hour before bedtime.

- Repeat the exercises from the Formative Practice learned in the attendings.

- Socialize online with family and friends with or without pictures.

- To get back into the routine the practice of satisfactory habits that were no longer performed during the pandemic.

- Decrease exposure to news concerning the pandemic.

- Study ways to enable remote work and income improvement.

- Ask for help from family members when there are difficulties with online activities.Specific guidelines for parents:

- Accompany the children in their school activities and help with any difficulties.

- Talk to your children about the new routine and include the children’sneeds in the new daily life.

- Organize the environment for remote work and study.

- Gradually encourage small actions by children toward their own autonomy and participation in household chores.

8.3 EFFECTS OF THE GUIDANCE OFFERED

- Decreased anxiety and emotional instability.

- Decreased stress and improved sleep and mood quality.

- Improved family relationships with reduced conflict.

- Increased contact with body reality and decreased body pain.

- Performing physical activities.

- Increased socialization, resumption of contact with family and friends.

- More organized and more satisfying routine.

- Greater problem-solving capacity and more assertive referrals.

- Validation of fatigue and implementation of rest moments.

- Increased motivation and confidence.

- Implementation of leisure moments, with online or face-to-face activities safely.

8.4 THE APPLICATION OF FORMATIVE PRACTICE AND ITS EFFECTS

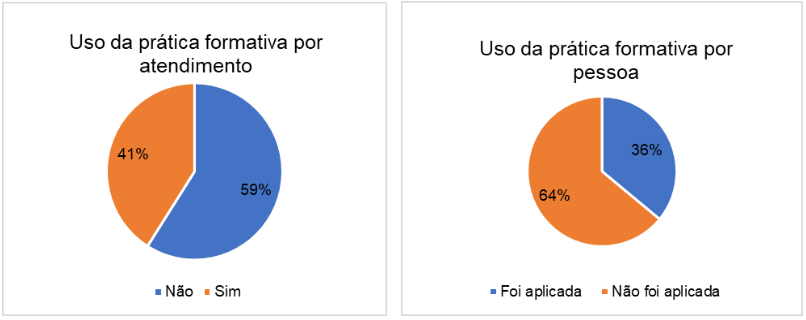

The Formative Practice was applied with 36% of the people, in 41% of the attendances.

The people who did the Formative Practice in the sessions reported repeating the exercises between meetings, which shows an appropriation of the tool learned. According to their feedback, by repeating the practice they learned to notice the levels of pressure they exerted on themselves, the way they exerted this pressure muscularly, and the emotional effect of this action. They also learned that they were able to decrease the intensity of the pressure and alter their emotional experience to create more calm and confidence. The experience of competence in emotional self-regulation was important and proved to be satisfactory.

8.5SOCIALIZATION DURING QUARANTINE

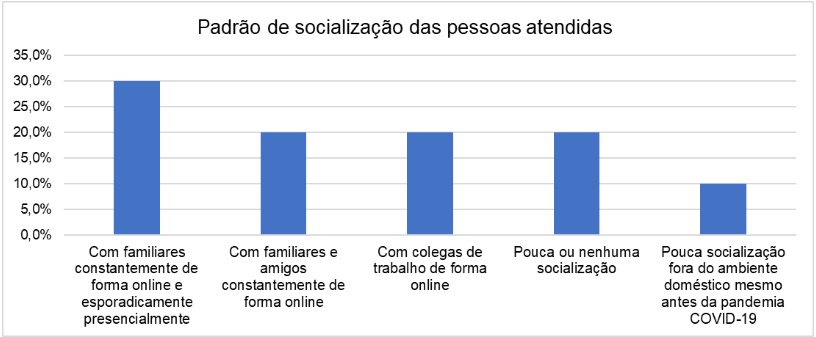

In the Project protocol there was a specific survey to understand the socialization pattern of people outside the home environment so that the professional would know their support network. The data is below:

- 30% were socializing only with family members, constantly online, and sporadically in person.

- 20% were socializing with family and friends constantly, online.•20% were socializing only in remote work.

- 20% reported little or no socialization.

- 10% reported that regardless of the pandemic they socialize very little outside the home environment.

8.6 GENERAL FEEDBACK FROM THE ATTENDANCES

All people said that the Crisis Services helped them create more satisfying responses to the problems they experienced during the pandemic, especially in terms of learning self-influence and problem-solving. The Crisis Services helped them to recognize the stress and anxiety also caused by the sudden change in daily life, especially the imposition of social isolation, and enabled them to implement small actions that significantly altered their experience of the situation.

The most valuable achievements reported were learning emotional management and building routines more appropriate to the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The practice of both generated an experience of greater calmness and competence in dealing with the situation.

Other important feedbacks were the learning of contact with oneself, generating an increase in self-knowledge, more tolerance, and calm to make decisions; a satisfaction with the practicality of the orientations received, which enabled the reorganization of the life dynamics, and the importance of having a space for conversation, welcoming, and support.

It was also reported that the meetings were valuable for having made possible the perception of personal difficulties beyond the pandemic situation, which generated motivation to change. In some peoplethe experience aroused the desire to continue the process, and they were encouraged to continue the work started in the meetings. Psychotherapy was indicated for 48% of the people, psychiatry for 8%, and physiotherapy, women’s group, and parents’ group for 4%. They were advised to look for health services or to recommend friends and family members.

Below are some quotes from the people served:

“I felt calmer”

“The conversations helped me to get more in touch with myself, and to learn how I push myself and how I can lessen my toughness. I also learned how I can be more tolerant and calm to make decisions.”

“From the conversation I noticed that my routine was unstructured and that there is a process to restructure it”

“I felt more confident and motivated to change”

“The appointments helped me to have hope and to realize that change is possible”

“You helped me realize that I can create small changes to feel less guarded and also how I can talk to my parents”

The consultations were mostly individual -91% -and only 9% in groups. Only three groups received registrations, Coming out of Isolation, Body Equilibration, and Parents Group, and these were for only one person in each group. Since groups were not formed, the consultations occurred individually within the framework of the group’s proposal.

9 ANALYSES

Human beings are endowed with innate responses for dealing with danger and threat. The “startle reflex” is one of these and is intended to cope with emergency situations or short periods of alarm (Keleman, 1985). This reflex generates changes in muscular posture, the body’s relationship to the gravitational line, body wall thickness, and pulse rate. Once the emergence is over, the body returns to its usual posture. However, depending on the duration and intensity of the situation, the reaction may endure and generate a lasting stress response. Lasting stress takes shape in anatomical patterns and extends to the dimensions of personal habits and social relationships (Keleman, 1985, 2007c).

The people assisted reported experiences of startle and fright in the face of uncertainty and abrupt change of routine, as well as a high level of anxiety, followed by fear and stress. Keleman describes stress and anxiety as patterns of emotional-anatomic organization expressed in the contraction of muscles and organs.

The prolonged period of exposure to threats and uncertainties during the COVID-19 pandemic favored the maintenance of a state of alertness and stress. The period of social distancing and isolation also generated intense feelings of loneliness, significant changes in daily habits, interpersonal relationships, and a difficulty in organizing functional routines in the face of the new situation, both at the individual and family levels.

It is understood that the responses of fear, anxiety, irritability, discouragement, and tiredness reported in the consultations were consistent with the prevailing situation and should be validated in circumstances such as this (2007c). However, the prolonged stressful situation was intensely disruptive for some people, which led them to seek the service offered.

The Formative Work developed the capacity for voluntary self-influence and made it possible to learn new responses. The reorganization of habitual behaviors, the regulation of effort, and the establishment of new procedures in daily life were fundamental to promote emotional stability. The structuring of well-defined routines within clear limits and the implementation of moments of rest between activities were very important for the reduction of stress and anxiety.

The practical guidance involving macro behaviors was well received and proved to be effective, offering reassurance, a direction for the future, and generating hope. The consultations brought about changes in people’s relationship with themselves and in the way they experienced the crisis in the pandemic.

The Formative Practice applied in 41% of the consultations proved to be an efficient tool to deal with the crisis. The learning of the Practice using voluntary cortical muscle effort (VMS) with micro-movements to alter emotional experience and behavior was very powerful. The exercise of self-influence through small changes in muscle intensity generated the experience of ability and competence. The possibility of altering emotional experience through micro muscular changes was experienced as a pleasant surprise by people.

During the sessions, people were able to reflect on their lived experience, their behaviors and family conflicts. The practice of reflection together with the therapist’s guidance helped them to reorganize their response to the situation. The development of self-knowledge and the capacity for self-influence positively affected people’s relationship with themselves, their family relationships, and the waythey dealt with the pandemic crisis. The ability to change one’s own state and behavior generated an experience of empowerment, an increase in self-confidence, and a decrease in anxiety.

We understand that the predominant demand for individual care (91%) was due to a preference for more privacy.

Considering the positive results of the interventions in a short period of time, it was evaluated that the strategy used in the consultations was efficient.

10 CONCLUDING REMARKS

The focal and short-term formative approach was an unprecedented challenge and an important professional learning experience for all team members. Working exclusively online was a new experience, which required the creation of new procedures and specific care and generated the acquisition of expertise. The online format also made it possible for the Project to extend to several states in Brazil and abroad.

The difficulties imposed by the pandemic were also a challenge for the Project’s professionals, whose team went through its own formative process in the construction of the work model. The supervisions, coordination meetings, and regular shifts were fundamental to structure and keep clear the framework and objectives of action. The structure created provided the professionals with an experience of belonging, stability and trust, and promoted a consolidation of the bonds between colleagues.

An important aspect was the recording of all the work through reports of the consultations. The short time of the project plus the challenges of the pandemic and the lack of a systematization of writing styles in the proposed framework caused delays in the delivery of reports and made it difficult to compile the data. Thus, we realized the need to objectify the structure of the report to facilitate the systematization of the data in future works.

The team evaluated the Crisis Care Project as effective and successful. The experience was enriching for the professional development of all involvedand for the community of the Center for Formative Psychology® of Brazil as a whole. It is considered that this service model may be used in other projects for crisis situations given its important social contribution in the midst of adverse circumstances.

The successful experience generated the desire to continue the work and motivated the team to create a new project: Tecendo Formas: an online Formative Service clinic.

Tecendo Formas offers individual and group services in the modalities of psychotherapy and complementary integrative practices. The Project has the proposal of making values flexible and proposes to make the access to the Formative Work possible for the population in general. Tecendo Formas has been operating permanently since 2021 at the Center of Formative Psychology® of Brazil.

Both projects make it possible to conduct research and clinical documentation on the Formative Work Methodology and to create models that can support other professionals and teams in their fields.

REFERENCES

Cohn,L. (2016, May 1). A Psicologia Formativa® de Stanley Keleman. Retrieved September 12, 2022, from https://psicologiaformativa.com.br/a-psicologia-formativa-de-stanley-keleman/

Cohn, L. (2007). Formative Psychology®: An evolutionary path. USABP -United States Association for Body Psychotherapy, 6(1), 39-43.

Keleman, S. (1979). Somatic Reality. Center press.

Keleman, S. (1985). Emotional Anatomy. Center press.

Keleman, S. (1987). Embodying Experience. Center press.

Keleman, S. (2007). A Biological Vision. USABP -United States Association for Body Psychotherapy, 6(1), 10-14.

Keleman, S. (2007b). The Methodology and Practice of Formative Psychology. USABP -United States Association for Body Psychotherapy, 6(1), 15.

Keleman, S. (2007c). The Somatic Shapes of Depression . USABP -United States Association for Body Psychotherapy, 6(1), 18-21.

Leave A Comment